Big 21st-Century Ideas the World is Counting on You to Know (Share More in the Comments!)

In a lecture I attended last year my professor prefaced a discussion of game theory with "and the concept of a prisoner's dilemma is one of those things I am confident saying you are not an educated person in any meaningful sense if you have never taken the trouble to understand or learn it. The idea that we can map out the conditions under which cooperators will defect given individual incentives, even despite the fact that the collective incentive can be to cooperate for a higher payoff, is so fundamental to understanding the problems of the 21st century (like Climate Change) that I think it's only fair that we set our bar/expectations for the educated person high enough that they would know this enough to be able to act on it."

This got me thinking: what else would a list of things every 21st Century person should know include? Pick any discipline you want, but try to meet my criteria. Here's mine! (A list like this is bound to sound opinionated and self-congratulatory because it's an attempt to list the things you think you already know but that many others don't, but for the same reason that the "rationalist" community has chosen a vaguely positive adjective for itself, and only aspirationally rather than narcissistically, I want you to put aside the self-conscious worry that you sound self-indulgent and just do your best to outline the greatest ideas an education can impart for someone aspiring to a true education)

Here goes nothing:

#1. The Revolution of Behavioral Genetics that has transpired over the latter half of the 20th Century and the first quarter of the 21st is of pressing relevance to the emerging challenges of our contemporary era. The basic thrust of this research begins with the fact that "Nature and Nurture" are alternatives of degree rather than alternatives of kind (a difference of degree being the answer to "how much?" and a difference of kind being the answer to "whether at all?"). It is actually logically impossible for a trait to be "purely biological," because DNA is just a biological program that specifies a developmental process within an environmental venue, and cannot specify that process down to a perfect, literally replicating level of precision (that is, even genetically identical monozygotic twins will have neurological differences, because although their bodies followed the same genetic program to achieve a developmental outcome, that program could not specify the precise location of every neuron and the other cell-types that compose the brain down to a square nanometer-for-square-nanometer replica.

As a result, the Lady Luck of chance variation has her way with the remaining details, and that's saying nothing about the many monozygotic twins who nevertheless do not share a placenta, inviting even more environmental differentiators into the mix!). Moreover, "influenced by biology" does not mean "created by biology" but rather "organized in advance of experience and exposure." Biology is often the container, and culture is the content. You are prepared by the biology for a lifelong process of experience.

The emerging science of behavioral genetics has upended our folk intuitions about nature and nurture, challenging even the notion that parenting styles determine lifelong outcomes in personality and intelligence and greatly de-emphasizing the importance of the "shared environment" (as opposed to the unshared environment and genetic endowments) in explaining individual differences (I recommend Judith Rich Harris's monumental The Nurture Assumption for a survey of the evidence of this maturing field of study).

It has often been said that parents who read books to their children at night and line the shelves with the classics of the English literary cannon are bound to have masterfully articulate children; but all of this was assumed regardless of the fact that a set of parents who take the trouble to enrich their child's environment are likely highly industrious people by temperament, and are also highly verbally fluent to have a fascination with books in the first place. Small wonder their child turns out to be a natural in English class!

People often wonder how something like vocabulary could be a high indicator of general intellectual ability, or why it is strongly correlated with mathematical and visual-spatial reasoning, because it seems to reflect the richness of one's environment rather than inborn aptitudes; but it turns out that verbally precocious youth will simply pick up and retain words faster, understand them in an intuitive and flexible way, intuit their relationship to others extemporaneously and do not have to be shepherded through Vocabulary 101, and seek out reading material and latch onto terminology by virtue of the sense of intellectual need that is provoked by a preponderance of intellectual ability (you will generally wish to flex the muscles that you have).

But does this mean we should be depressed and fatalistic and give up on parenting? Well, first of all, parenting is about creating a relationship, not a person! The overbearing obsession with bombarding kids with Mozart in the car and chess club after school (even after they complain about it) so that they will grow up to have high intelligence is unhealthy and scientifically misguided. Only newlyweds thinks that they can change their spouses; the purpose of the relationship is love, not to strive to micromanage their innermost and stable and largely inherent qualities. But, second of all, the punchline of the revolution in behavioral genetics research is that the role of the [shared environment](https://dictionary.apa.org/shared-environment) as opposed to the [nonshared environment](https://dictionary.apa.org/nonshared-environment) has been exaggerated, not that the environment does not matter. Peer groups are extremely formative, for example, and parents still have considerable control over that.

But just as there can be no biology without culture, there can be no culture without biology. One legacy of the behaviorism movement in psychology was the idea that language has no innate structure, that we are born with blank slates, that everything is a product of experience, and that if the slate is blank you might as well grab a pen (leading to some pretty bizarre parenting advice and a massive overstatement of the potential of public policy to engineer every social outcome we can fondly imagine). Noam Chomsky replied with the single most influential book review ever written as an undergraduate at the University of Pennsylvania with his theory of universal grammar, whereby he demonstrated that children acquire language with the aid of a bevy of inborn, biologically predisposed devices that are culturally universal.

For example, all children are born with the capcity to make the rudimentary phonetic sounds that are employed in various languages, with toddlers playfully trilling and rolling their "r's"; culture, however, prunes this down into a useful set of linguistic building blocks by signaling to the developing brain that hears their chattering parents whether the "r-trill" is essential to their language or not: if not, the ability usually vanishes, and may be difficult or impossible to reacquire in adulthood. If a trait can be found in all cultures of any significant size, especially those that have been insulated and isolated from contaminating influences (in the scientific sense of making the identification of causes and effects ambiguous), then it stands to reason that there is a substantial biological component to the trait (hold the environment constant, and if you still see differences, the genes are at least partially responsible, and vice versa; I say partially because in practice you can never hold the environment constant).

What is so terribly interesting is that we have found far more cultural universals since Chomsky wrote his earthshaking debut in the field of linguistics. It was once thought that human emotions are culturally idiosyncratic and non-universal, or that facial expressions have far more differences than similarities and do not generally correspond to the same emotions cross-culturally. This has been flatly refuted by a massive raft of scientific evidence. Anthropology, once a field scandalously committed to exaggerating the fundamental uniqueness of different cultures as a convenient source of dissertation-fodder, has now begun to embrace the litany of similarities. Donald Brown published one of the most widely-referenced lists of cultural universals, from which I have excerpted the following:

"the existence of and concern with aesthetics, magic, males and females seen as having different natures, baby talk, gods, induction of altered states, marriage, body adornment, murder, prohibition of some type of murder, kinship terms, numbers, cooking, private sex, names, dance, play, distinctions between right and wrong, nepotism, prohibitions on certain types of sex, empathy, reciprocity, rituals, concepts of fairness, myths about afterlife, music, color terms, prohibitions, gossip, binary sex terms, in-group favoritism, language, humor, lying, symbolism, the linguistic concept of “and,” tools, trade, and toilet training." [The real list is considerably longer.](https://condor.depaul.edu/~mfiddler/hyphen/humunivers.htm)

Big Idea #2: Actuarial Psychology: The integrity of psychometric operational definitions; the measurability of allegedly infinitely idiosyncratic and subjective traits like intelligence and personality.

I think it is crucial that people become disabused of the idea that personal qualities and intersubjective traits like personality and intelligence are these amorphous, impenetrable concepts that could never be meaningfully measured or described with operational constructs. If you want to believe that, then consider that it is largely by endorsing and exploiting the psychometric worldview that corporate titans like Google, with its ingenious data-science-based advertising, and Amazon's brilliant personalized-preference-modeling have been able to rake in an unfathomable bottom line and now exert arguably more influence on the dynamics of our present day than entire countries.

Every day, you are being molded, shaped, and influenced constantly by a lifelong process of psychological collation and quantitative profiling; how much more pliant and ideal a target you will be if you do not have a sense of the forces that are arrayed against you or the methods they are using to achieve unprecedented levels of consumer control. If this sounds dismissably conspiratorial, then I urge you to consider the ominous findings, published in the most recent edition of the prestigious scientific journal Nature, showing that for a sample of over 1,500,000 faces an algorithm predicted self-identified political party affiliation with 72% accuracy (and 69% accuracy, still considerably above chance, even after controlling for markers of age, ethnicity, and sex). (See more here: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-79310-1)

The psychometric worldview is also essential because it allows for actuarial and algorithmic prediction making for life outcomes we care about (like earning potential, marital satisfaction, criminal recidivism, who we should parole and who we shouldn't, whether there is any point in keeping violent criminals in jail beyond the age of 42 + or - 5 years).

As for personality, some sense of the Five Factor Model of Personality would be helpful, as well as a basic survey of the evidence for organizing personality along five (or so) major dimensions (O.C.E.A.N.: Openness to Experience/Closed, Conscientiousness vs Impulsivity, Extraversion/Introversion, Agreeableness vs Antagonism, Neuroticism vs Emotional Stability). These are essential to our toolkit because they help us speak with a richer vocabulary when explaining why it is that people vary in their talents and dispositions, which is going to be important if you ever find yourself needing to interact with people and cooperate toward a complex goal, or build a team to solve a problem or realize an entrepreneurial idea.

Some impression of the sheer predictive power, validity, and lifetime stability of assessments of intelligence like I.Q., particularly those that take inspiration from Howard Gardner's theory of Multiple Intelligences, are crucial to the general toolkit I am hoping impart with this list. Briefly, there are a variety of special cognitive niches, and they are generally correlated so that a specialist in the 99th percentile on one is also likely to be a generalist in the 50th-or-greater percentiles on the others.

Let’s explore a few important subtypes:

The Visual-spatial sense reflects your sense of space and intuitions about distance, as well as your ability to extrapolate geometrical patterns and intuit the progression of an object that changes according to a rule-governed sequence.

The Verbal/Linguistic subtype reflects your command of a primary language, the ability to express oneself articulately and clearly, the ability to define words in contrast with their antonyms and, more challengingly, with their synonyms, etc.

And you probably have a pretty rough idea of what is captured by the Quantitative/Mathematicalsubtype, especially if you have taken a state-mandated educational achievement exam or the SAT and ACT college-entrance examinations. (And this is not an exhaustive list: intelligence tests include batteries of standardized assessments of processing speed, your general fund of information, and various aspects of your working, short-term, and long-term memory.)

Big Idea #3: The consequentialist/utilitarian framing of justice as an antidote to that great legacy of religious traditionalism, the retributive theory of justice, which I want to (somewhat facetiously) characterize as "the idea that there is a cosmic scale of rights and wrongs that gets thrown out of balance by wrongdoing, and which only a righteously deserved PUNISHMENT can restore to its former graces." This "punitive," deontological, punishment-for-punishment's sake attitude is the ultimate sentimentalizing moralistic bias, and in practice falls pretty squarely into the contrast between the empirical, evidence-based view of public policy and criminal justice and the knee-jerk, gut-feeling, sanctimonious fetishism of so much of contemporary society. I'll let you guess which I think is which.

Big Idea #4: The Unmerited Nature of Meritocratic Success: The great winners of the 21st century will be meritocrats. Exceptional, technically gifted, luminously brilliant, zealously hardworking meritocrats. They will also be the winners of various genetic and environmental lotteries: nobody chooses their parents, which prenatal hormone exposures occur throughout their mother's pregnancy, whether their early childhood environment is characterized by high levels of stress and a general absence of a varied and stimulating, intellectually enriched environment, and nobody chooses their genes.

There is no escaping the fact that conscientiousness, the personality trait which underlies industriousness and a general temperamental pressure to strive, and which at its extremes becomes an unforgiving call to perfection, is a highly heritable trait that is also likely a highly inherited trait (heritability being the explanation of differences or variations in human traits in the general population in terms of the contribution of genes from parents to offspring, and inheritance being the endowment of individual characteristics to individual children through biological parentage; for both of these measures of implicating biology, there is an enormity of evidence that conscientiousness has a substantial genetic component: parenting and adoption studies, and genome wide association studies that have become possible in the last two decades by virtue of the comprehensive mapping of the human genome).

But you may reject this evidence and prefer instead to say that hard work and intelligence (to the extent that we have been able to measure it in a standardized, statistically normalized way) are purely environmental. Even that would not give a foothold to the false ethic of our meritocratic culture, because no one chooses their early childhood and prenatal environments, and even later few people can change the likely environmental culprits without opposing external forces lending a hand (like sane egalitarian, utilitarian, and empirical public policy) that account for the variability of intelligence between individuals.

This is not to say that we should no longer reward hard work, or allot social prestige to the winners of competitive enterprises, or prefer an average surgeon to a peerless extraordinaire, but it does mean that we should foster a spirit of humility in our elite culture, discourage class-insulation, break up insulated pipelines to institutionally guarded success (as with the five American zip codes that make up a substantial contingent of the undergraduate class at Ivy League and other elite universities), and, crucially, follow out the obvious political moral that it is wrong to force someone to live with the consequences of events outside of their control.

That is to say, improve the external factors that we can improve which account for the predictive advantages differential psychology research has unveiled, and improve the conditions of people who are simply not talented enough to make it (rather than setting a bare-minimum floor, like "here's enough not to starve, but good luck with your rotting teeth and horrendous chronic orthopedic problems that nevertheless call for elective and uninsured healthcare interventions").

Big Idea #5. The Selfish Gene: Defended, reimagined, and popularized by Richard Dawkins, the gene-centric view of evolution that emphasizes that the level at which evolution by natural selection takes place is the level of the gene, as opposed to individual-organism-level framings or (worse still) for-the-good-of-the-species framings. As an aside, people who are quick to dismiss evolutionary psychology are just as likely to pretend to have read this book, in my experience, which is odd because I would consider it one of the greatest works of evolutionary psychology (although it is obviously much, much more than that).

Big Idea #6: The Utilitarian, Quantitative analysis of public policy, which Steven Pinker has amusingly defended by saying “despite its nerdy aura it is the morally enlightened one because it treats all people as though they have equal significance relative to the outcomes”. Along with this I would add the general (and deliberately vague, but still no less essential) orientation of our public policy debates around "Do the Overall Benefits Outweigh the Overall Costs?"; "Has a gradual process of experimentation and representative comparisons demonstrated the benefits of this proposal, or are there likely to be unintended consequences at scale?"; "How does this compare with the available alternatives, and have we taken sufficient care to lay these out before endorsing a greater of two goods or a lesser of two evils?"; "What is the final, net outcome of this policy likely to be, and if we cannot even begin to answer this question should we continue to entertain it?" That is, the opposites of questions like "but does this fit my moralistic, deontological idealization of what my gut feelings and twitter sloganeering tell me is important? Is this exactly and unpragmatically what I want in exactly the way that I want it?"

Big Idea #7: The Myth of Pure Evil: The ideas that Jonathan Haidt lays out in his *The Righteous Mind: Why Good People are Divided by Politics and Religion.* That there is such a thing as different political personalities to which our biology and cultures predispose us (not in the outlandish sense of the body following a developmental program via our DNA to synthesize our party registration out of thin air, whatever that would mean, but in the sense that we can inherit general temperaments that motivate overall attitudes toward moral and political questions, or at least patterns of group-affiliation that will land us in cultural milieus that endorse certain political and moral ideals, i.e. urban living and college-attending partially as a consequence of high openness to experience vs. rural living and staying local as a consequence of less openness and more traditional feelings toward familial and community loyalty), which can cause us to assign different moral weights to the various "moral foundations" that motivate our social and political priorities. In other words, the idea that when someone disagrees with you politically, it may not be so much a reflection of their sadistic, unfeeling, sociopathic disregard for Truth and Goodness, but a recreation of the reasons you believe much of what you believe (beliefs as a loyalty badge, a social signal, an aspect of social belonging, and an outgrowth of different moral intuitions, etc.).

Edit 2: some others that I want to elaborate on with a blurb as I have been doing so far but don’t have time for right now. I thought I may as well include them so I remember to do it later:

Big Idea #8. The environment of evolutionary adaptedness: The idea that the traits we evolved are largely the product of evolution by natural selection in an ancestral environment that is very different from the world we live in today, helping to explain many of the puzzles of why we have the quirks we do and suffer from so many incompetencies that are deficits in the world we live in today (like many forms and severities of ADHD) but were likely things working “as intended” in the past, which may be an inspiration for some compassion for people who don’t fit into the bizarre and evolutionarily remote world we find ourselves in now and for which we were not "designed".

Big Idea #9. Graham Oppy's concept of rational belief-formation as a process of "worldview comparison" where people follow the following dictum as strenuously and honestly as possible: "the purpose of a belief, and the worldview beliefs make up, is to explain a maximum amount of data with a minimum of theoretical commitments."

(For persnickety philosophy buffs who worry that this is just an overstated version of Occasm’s Razor: He reconciles this with the idea of non-referentially justified, properly basic beliefs, and please note that he encourages a spirit of minimalism but not nothing-whatsoever when it comes to parsimony and Occam's razor)

Big Idea #10. Adding to that, (A Useful Shorthand of) Bayes Theorem, and if not the whole theorem with every bell and whistle in mind, then at least the basic idea that you should estimate the likelihood of something based on a careful combination of 1. asking yourself what the world would be like if this idea was true, and comparing the world we actually live in with that world, and 2. the notion that a "prior" can exist independent of the evidence or hypothesis presenting itself to us in a given situation that should inform the outcome of our probability assessment.

(If I am mutilating the theorem, please let me know so that I can correct it and become more of an educated person!)

Big Idea #11. The fact of the availability heuristic and other relevant cognitive biases that leave us vulnerable to a knee-jerk pessimism about the world in general (or at least having the wrong policy priorities, regardless of where you come down on the optimism and pessimism debate). A poll in 2016 found that most American voters cited "terrorism" as the #1 greatest threat to American life at the time of the presidential election.

I want to offer an alternative to this tendency to estimate probability based on imaginability rather than the frequency of real-world occurrences with Steven Pinker's notion of "informed, rational optimism," which argues that news media follow a policy of "if it bleeds, it leads" that distorts our perception of just how hopeless things are and implicitly encourages a jaded, nihilistic, "eat drink and be merry for tomorrow we die" or "take a wrecking ball through the 'establishment,' erase it and start over because nothing is working (what 'drain the swamp' turned out to mean in practice)" attitude.

How many times have you heard that the world is just getting worse and worse and worse on every metric relevant to progress, that our best days are behind us, that if only we could return to year X things would be so much better? Often, Franklin Pierce Adam's quip that "nothing is more responsible for the good old days than a bad memory" is vindicated by our tendency to become amnesiacs with respect to progress achieved, once it has been achieved, and neurotics with respect to progress still yet to be attained. This is married in a gross symbiosis with our tendency to expand the definition of our words for progress to reflect our moral deficits by virtue of our moral gains: "bullying", "assault", and so on (and I'm not complaining about the intentions, obviously, but their unintended effects) have followed a pattern of us mistaking our rising standards for our plummeting conditions.

Combine this with the fact that progress generally follows the law of the accumulation of marginal gains, and you have a recipe for an incorrigible pessimist. The news is about what happens, not what doesn't happen, and the worst things happen suddenly, but the best things happen gradually. A single downtick in an otherwise stable trend of progress is "news" because it is "new," and a reporter never says "I'm here reporting live from a country that hasn't broken out in civil war." The breakneck rapidity and inherent, cyclical amnesia of the "news cycle" blinds us to the steady accumulation of gradual successes and small victories that have made the convenience, amenities, increasing richness and safety of modern life possible.

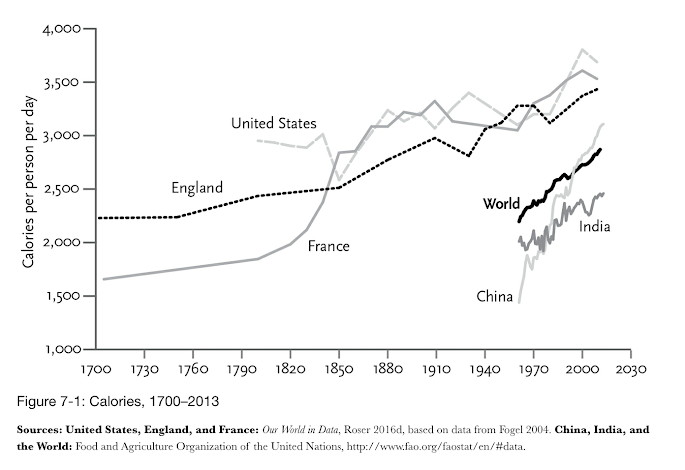

"Max Roser points out that if news outlets truly reported the changing state of the world, they could have run the headline NUMBER OF PEOPLE IN EXTREME POVERTY FELL BY 137,000 SINCE YESTERDAY every day for the last twenty-five years... In 2000 the United Nations laid out eight Millennium Development Goals, their starting lines backdated to 1990. At the time, cynical observers of that underperforming organization dismissed the targets as aspirational boilerplate. Cut the global poverty rate in half, lifting a billion people out of poverty, in twenty-five years? Yeah, right. But the world reached the goal *five years ahead of schedule*. Development experts are still rubbing their eyes. Deaton writes, 'This is perhaps the most important fact about wellbeing in the world since World War II.'" -- Pinker, Steven. Enlightenment Now (pp. 88-89).

Well, resources like [ourworldindata.org](https://ourworldindata.org) or Pinker's book *Enlightenment Now: The Case For Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress* reply by saying there is a rigorously quantitative and empirical way of addressing this question that identifies the spheres of human progress and awards points to each side (optimism/pessimism) based on *actually counting.* 175 graphs on everything from measures of physical health/mortality, violent crime, and accident deaths to subjective but operationally defined things like life-satisfaction, happiness, boredom, and a sense of meaning and purpose will help you realize that, regardless of where you come down on this debate, there is a far more evidence-based and subtle way to have it.

It should go without saying that none of this is to say that progress is inevitable, that progress is happening fast enough, or that progress will happen on its own without a rigorous and constant exertion of the systematic forces that have made it possible. It is also not to relieve us from individual and collective responsibility, as one existential catastrophe is all it takes to wipe out the gains of humanity in a relatively short period of time. So, my ideal of the educated person should have some intellectual permission to be optimistic, but none whatsoever to rest on the laurels of success or become negligently self-satisfied.

Big Idea #12. The causes, correlates, and consequences of the decline of all kinds of human violence throughout history. Now, to be absolutely clear, I am only referring to what explains declines of violence when they actually happen; I am not endorsing Pinker's view that the entire story of human history is one long decline (with a few interruptions/upticks/rouge data points in an otherwise clear trend running back to even the hunter-gatherer pre-agricultural era) of violence, although I think reading The Better Angels of Our Nature was one of the best things I have ever done for my appreciation for the importance of thinking about violence in a rigorously interdisciplinary way (he ambitiously integrates the sociology/neuroscience/human behavioral biology/psychological adaptationism, a term I prefer to evolutionary psychology but which I understand is controversial/history/game-theoretical/and economic lenses on human violence and deviant behavior).

These are essential because if we know what we have done well, we can continue to deliberately deploy the known causes of the decline rather than reinventing the wheel or retrying solutions with a checkered and discrediting history. For example, Pinker addresses the following religious and conservative theories in a huge discussion of the European homicide decline with the following thesis: "Do you think that city living, with its anonymity, crowding, immigrants, and jumble of cultures and classes, is a breeding ground for violence? What about the wrenching social changes brought on by capitalism and the Industrial Revolution? Is it your conviction that small-town life, centered on church, tradition, and fear of God, is our best bulwark against murder and mayhem? Well, think again. As Europe became more urban, cosmopolitan, commercial, industrialized, and secular, it got safer and safer."

Big Idea #13. Robert Sapolsky's impressively interdisciplinary model for analyzing and explaining human behavior (which he sets out in his monumental book Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst, which develops and responds to many of the ideas Pinker lays out in *Better Angels).* In this book, Sapolsky integrates several disciplines in the effort to explain our worst behaviors, such as the worst kinds of human violence. (Although the benefits of this book go far beyond just addressing the same issues I broached in #4.)

To me, this book is really just an ode to the modern synthesis of neuroscience, endocrinology, psychology, evolutionary biology, genetics, game theory, and more as an attempt to explain and characterize human nature with a scientific visual aid. He charts out the steps of explaining behavior from: one second before (neuroscience), seconds to minutes before (psychology), hours to days before (emphasizing things like endocrinology), days to months before (more on human behavioral biology), years before (the influence of prenatal and perinatal events on life outcomes and personality), centuries to millennia before (genetics, evolutionary biology, evolutionary game theory). This is, by definition of being on this list, one of the best books I have ever read and I cannot recommend it more emphatically.

Big Idea #14. Edward Wilson and C.P. Snow's idea of Consilience, or the unity of knowledge: the idea that the disciplinary divisions that separate fields of knowledge say much more about the logistical limitations of our universities and institutional knowledge than it says anything about the nature of the real world which science and academia attempt to understand. This merges nicely with Sean Carrol's idea of emergent naturalism (also "poetic naturalism,"), which arranges each field of study into a hierarchy of "most fundamental to least fundamental" but not "most important to least important."

For example, history could be thought of (and in the opening chapter of Yuval Noah Harari's *Sapiens* he embraces this framing of history) as the level of analysis that comes after physics, chemistry, biology, and anthropology have told their stories and assumes the existence of humans and cultures that change. Each discipline sits on the shoulders of the other giants, but that is not to say that any are less important than the others or somehow less valid. For example, imagine trying to explain the causes of WWII in terms of quarks and the position, velocity, spin and magnetism of every particle in the universe. It wouldn't be a clarifying analysis, even if it would ultimately be true in its own way.

The following is an excerpt from my blog post, “Big Ideas Every 21st Century Person Should Understand and Doesn’t at Our Peril”

15. Effective Altruism [The fact that](https://www.ted.com/talks/will_macaskill_what_are_the_most_important_moral_problems_of_our_time/footnotes?language=en) the difference between the least effective charities and the most effective charities is an enormous, oceanic difference, and that there are empirical/evidential ways of determining [which is which](https://www.givewell.org/charities/top-charities). The fact that charity is not necessarily a false solution to contemporary problems, and that individual giving can actually change the world if directed according to the priorities of data science rather than the priorities of our gut-feelings and folk moral psychology.

I.e., the fact that a donation till with the face of one pitiful, hungry child receives several times more charitable contributions than a till emblazoned with five pitiful, hungry children. Or the fact that anti-milarial netting, as unromantic a solution as that may seem, is generally exceptionally more effective than more melodramatic or cute journalist-bait “solutions,” [like the now-infamous and celebrities-including-f**ing-Beyoncé-endorsed merry-go-round water pumps](https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roundabout_PlayPump) that turned out to complicate the logistics of pumping water in needy African villages, were not in fact an improvement on the cheaper and more cost-effective conventional water pumps, and quickly became yet another source of drudgery for the globally poor, with teams of women rather than the intended children at play arduously pushing the carousels in what looks like a distinctly not-fun process, the recreational implications of the [flowery, bright red-and-green-pastels](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/proxy/AVvXsEg64PdNNzxiFFzPI8WCRxXDLhRz2319YU5ebthUiD11o-is9NtICavZ76XjywGTNBYGoKljfpJsVY-u6p4FrnQn_HX4_ayNI1s7AykV5xqcE0MlZrcLVIthI5MGzvDOHinVmfEomE2wvCoMlBfAfb5V-VzcBfIvxEZTx7XKBcy2cmxhGvb5I8-PW-xwapbKYfqVaAs2FppOhpWQuvMhMjU=) just adding a moral insult to an economic injury).

You really have to see it to believe it. It’s so awful it’s almost morbidly funny, or it would be if it weren’t for the depressing facts surrounding it and the fact that [it’s still going strong a decade and much-scathing-criticism later.](http://www.playpumps.co.za)

And I can tell I should add something on the following three but need to get some sleep first before being back at it tomorrow!

To Be Continued At Some Point Today or Tomorrow:

16. Anti-Fragility:

17. Hedonic Treadmill:

18. Network Theory:

19. Reciprocal Altruism:

This list is getting a little long; I will come back later to add things, but I skipped lunch to write this! Anyways, I think this will be enough to get the ball rolling. Tell me what you think in the comments!

Comments

Post a Comment